For the past two years, Empower Missouri has been spearheading research into the practice of private probation in Missouri, to better understand its scope and implications for policy reform. Missouri is one of 12 states to utilize the controversial practice of private probation. Private probation is used in some counties to outsource supervision for misdemeanor offenses to private companies, rather than providing probation supervision through the county courts. Financially strapped court systems may see private probation as an attractive alternative to internal programming. Local courts are decentralized, with every county operating independently and entering into contracts with private probation providers as they see fit. This industry is unregulated, meaning that there are no standards for fee structure, services offered, or staffing requirements. The fines and fees levied on individuals on private probation can quickly add up, from monthly supervision fees to additional costs related to classes, drug tests, and more.

Private probation was codified into Missouri law in 1992 with RSMO 559.600, granting circuit and associate circuit judges the authority to enter into contracts with private entities to offer supervision services for individuals sentenced to probation for misdemeanor offenses. The fee structure of private probation in Missouri can vary widely depending on the sanctions that a specific company imposes on those on their caseload. The monthly supervision fee in Missouri is capped at $60 a month, but each service that someone is mandated to participate in carries an additional cost. For example, an anger management class can cost up to $800, while other classes can cost $50 per session, without having a set distinction on how many classes a participant can take.

Mass Supervision and Privatization

The rise of private probation in Missouri coincides with a national trend of a widening net of correctional supervision measures. Since the late 1980s, America has been in an era of mass incarceration, and now we have entered an era of mass supervision. Approximately 3.7 million people in the United States are on community supervision (probation or parole, also referred to as community corrections), nearly double the number of people who are incarcerated in prison or jail. Despite the large number of people on supervision, the many problems associated with parole and probation do not receive nearly as much attention as incarceration. It is important that policymakers and the public understand the connection between these systems of supervision and mass incarceration; alternatives to incarceration are not inherently less punitive than incarceration. This line of reasoning can lead to an over-reliance on community corrections, rather than seeking solutions that do not replicate the harms of mass incarceration.

As the scope of community corrections in our country has grown, so too has the proliferation of privatized services within the criminal legal system. From tech companies such as JPay profiting off of the email communications of those incarcerated in Missouri prisons, to supervision services such as EMASS (Eastern Missouri Alternative Sentencing Services) that market electronic monitoring services to county courts, the criminal legal system has provided fertile grounds for companies seeking to profit. The private probation industry exists at the intersection of mass supervision and privatization, but much about the practice in our state and how it impacts Missourians remains unclear.

Phase 1 Research: State-Wide County Survey

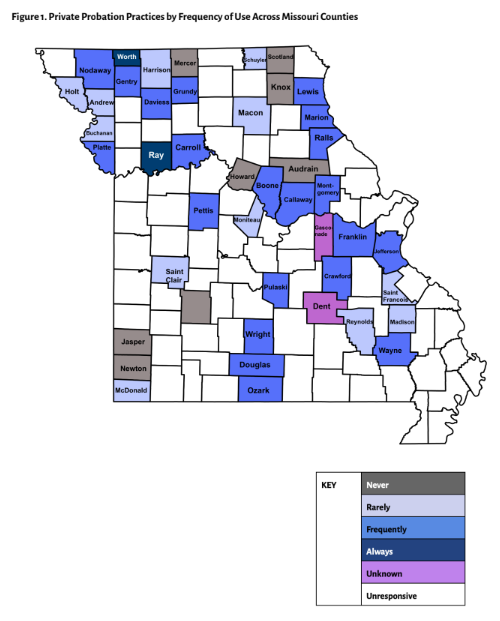

In the fall of 2022, Empower Missouri conducted a state-wide survey to determine the prevalence of private probation in Missouri. This initial research had several key findings:

- Private probation is a widespread practice across Missouri courts. Over three-fourths of the responses received (i.e., 35 of 45 counties) reported contracting with private entities to provide supervision services in at least some instances.

- In over half of these counties (23 counties; 51%), local courts are relying on private supervision entities to provide services “frequently” or “always”.

- Private entities provide supervision services in counties across the state, regardless of geographical location. Of the data collected, there were no apparent geographical patterns in the frequency at which private probation is used.

- However, discrepancies in the reported frequency of use between neighboring counties suggests significant variation among courts in the rate at which private entities are used for supervision services.

- There are at least 27 different private entities providing court-ordered supervision services across the state.

- Survey results echo findings in the literature that suggest there is no tracking of these companies, and no data to speak to the ways in which people experience their services, leaving their operations largely unchecked.

These findings were limited by the response rate, and only represent a third of Missouri’s counties. However, the widespread geographic results suggest that the practice of sentencing people to the supervision of private entities, who operate separately from the court or state correctional programs, is widespread in Missouri. You can read the final report from Phase 1 of our research in its entirety here.

Phase 2 Research: A Closer Look

In building on the first phase of research, we decided to take a deeper dive into the practice of private probation in a few select counties. We are conducting interviews with key individuals such as judges, private probation company employees and owners, and individuals on private probation, as well as observing court proceedings for private probation dockets. This research is currently underway, but some preliminary themes have emerged.

- Conflicts of interest can easily arise: Many private probation companies provide a laundry list of services, and some require clients to use their services exclusively, rather than being able to shop around for the most affordable option. Even when the option is not explicitly stated, it can be implied, as individuals may feel compelled to use the agency’s services to avoid potential probation violations. This restriction eliminates the client’s freedom to choose services that might be more cost-effective or convenient for them. Conflicts of interest between the companies and the courts exist as well: in one interview with a judge, the judge stated that some companies give gifts, such as sports tickets, to private attorneys that represent misdemeanor clients in court to incentivize the use of their company over others.

- Judges can use discretion to match sanctions to the individual and reduce unnecessary hardships: In one observed case, a defendant on private probation was issued an arrest warrant after he took off his ankle monitor. The defendant told the judge that he took off the monitor as he was unable to pay the GPS fine, which was $30 a day. The judge in this case, knowing the defendant is faced with financial hardship, reinstated his electronic monitoring but, over the state’s objection, through a free electronic monitoring system rather than through the private company. While judges have this discretionary authority, some might not utilize it, meaning that the experience of an individual on private probation can vary greatly depending on their assigned judge.

- Even in counties that utilize private probation, support is mixed: Just because a court system uses private probation does not mean that all the actors within that system support it. In an interview one judge said, “Unfortunately, these companies provide a service that the courts need. Unless the state or the county steps up and provides these services, we have to use these private companies”. He went on to say that if misdemeanor probation was controlled by the county, It would be a more fair and equitable way to manage those on private probation, as it would allow for better supervision. Any fines and fees collected would go back directly into funding the county sponsored probation. Court actors may be potential allies in stemming or regulating the practice of private probation.

Next Steps: Continued Research and Policy Reform

There are several bills that have been filed thus far in session that would address this issue. HB 1971, sponsored by Rep. Alex Riley, and SB 1227, sponsored by Sen. Barbara Washington, are both bills aimed at reducing the scope of misdemeanor probation, and in turn private probation, in Missouri. These bills would limit the maximum amount of time someone can be sentenced to misdemeanor probation from two years to eighteen months, and limit the use of drug testing for probation when the charge is not drug related. We will keep advocates informed throughout the legislative session about any opportunities to testify in support of these policies. We are working with partners to develop legislative language for future bills that would impose some regulations on the private probation industry, including basic tracking of what companies operate where and how many clients they supervise.

In addition to legislative advocacy, we will continue to expand upon our previous research in painting a clearer picture of the use of private probation throughout the state. Future reports, findings, and informational materials will be shared with advocates as they become available.

Additional Resources

Set Up to Fail: The Impact of Offender-Funded Private Probation on the Poor

For further reading, see Empower Missouri’s previous three part weekly perspective series on Private Probation:

Missouri’s Privatized Probation Services – Part 1: What is private probation?

Missouri’s Privatized Probation Services – Part 2: What’s the Problem?

Missouri’s Privatized Probation Services – Part 3: What Can We Do?

I need your help I believe the private probation in cape county has violated my rights ,I need someone to contact me please and God bless

Taney, Greene, Christian, and Stone definitely use private probation services for misdemeanors. They are all a racket.

Douglas, Wright, and Webster too, Douglas county’s, judge Boch, exclusively and in almost every case or bond release, uses Court Probation Services (CPS). My friend took a felony plea deal, to stop being charged, he still owed close to $600, he’s close to being able to be discharged from Felony probation, and he won’t get off until that’s paid. The fines, fees, and court costs amounted to about half that. Another on bond release, had to check in once a week, wasn’t told he had to pay anything. Goes for over 18 weeks, once a week, gets a text. the text says, that your over $180 behind, and anything over $100 is a probation violation, and you might go back to jail. He argued the fact they never told him, and was given no paperwork to state what and why he has to pay. why 18 weeks had to pass before getting told and threatened with jail. He paid over the phone that day, next time at court, asked to be released from checking in with CPS and explained what happened. Continued on calling every week and going in once a month. Still hasn’t been told what that is costing him. No signage in their building has what they’re fees are for or what it will cost. CPS and other private probation companies, are their own “mafia” and they buy off everyone who would care about this issues. I would estimate how much they’re making but they aren’t required to report their numbers or profits, contributions to judges, prosecutors, or any other office. Of course the state does, but since they pay they’re business taxes, like marijuana, they won’t give two shits about the poor being extorted into selling organs on the black market, the way my friend plans on paying his. Not joking.

They do that in Shannon County also they will set people with outrageous bonds or no bonds at all then when people actually can bond out the slap this private probation crap on you either ankle monitor or weekly drug testing people can’t afford that shit and the drug test mouth swab nor urine tests are accurate I know alot of people that took them and were clean and those test said positive they won’t retest ya nor do they send any of them to a lab to be confirmed they just write ya up send it to the judge and send you back to jail this time with a no bond warrant they don’t care if their test are faulty it’s their way of making money it’s all corrupt down here from judges, prosecutors, attorneys and cops! We the people do need help it all needs to be investigated!!!!