This session, five bills have been filed pertaining to funding for the Kansas City Police Department. For those who are not familiar with the issue, here’s a quick primer.

The Situation in KC

Kansas City is the only municipality in Missouri that doesn’t currently have control of its own police department. Under Missouri statute, the Kansas City Police Department is governed by a five-person Board of Police Commissioners, four of whom are appointed by the governor and one of whom is the duly elected Mayor of Kansas City. Additionally, the City of Kansas City is required (under Missouri law) to spend at least 20% of their budget on policing.

Last year, the KC City Council sought to designate $44M within the total $240M police budget to a “community services and prevention fund.” That money would have funded community engagement, outreach, prevention, intervention, and other public services. Ultimately, the police board sued Mayor Lucas over this attempted designation and won, because the judge in the case ruled that the city violated state law by making changes to the KCPD budget without the permission of the board.

Now, in direct response to this controversy, a group of Missouri legislators are seeking to force Kansas City to spend at least 25% of their budget on policing, a 25% increase to the existing budget. This represents a difference of approximately $87M. However, Missouri’s constitution currently forbids the legislature from requiring municipalities to fund new or increased services without a state appropriation to pay for those services. So, the legislature is seeking to amend the Constitution to allow them to establish minimum funding for law enforcement in any municipality that it deems necessary in order to prevent “defunding the police.”

And this brings us to the heart of the issue.

Finding Common Ground

As a state and as a nation, we have reached a level of polarization that is preventing us from having rational conversations about issues that are important to all of us. Police funding is one such issue.

Rational people can agree that communities benefit from the protection and service of law enforcement officers. We can disagree about tactics used by some police officers or transparency of some police departments. We can recognize and seek to improve bias in policing that is regularly demonstrated in instruments such as the Missouri Vehicle Stops Report. Still, if I’m at a store and there’s a robbery in progress, I want the police to respond. If I’m at a concert and a madman starts shooting indiscriminately into the crowd, I want the police to respond. If there is a serial killer or rapist stalking my community, I want the police investigating, finding, and arresting that person.

I know that there is a small contingent of people who believe in a utopian future where police are no longer necessary. I love that dream. But I don’t believe that I will live long enough to see it come to fruition. In our current reality, we need the police. However, this doesn’t mean that we need the police to do everything they are currently doing.

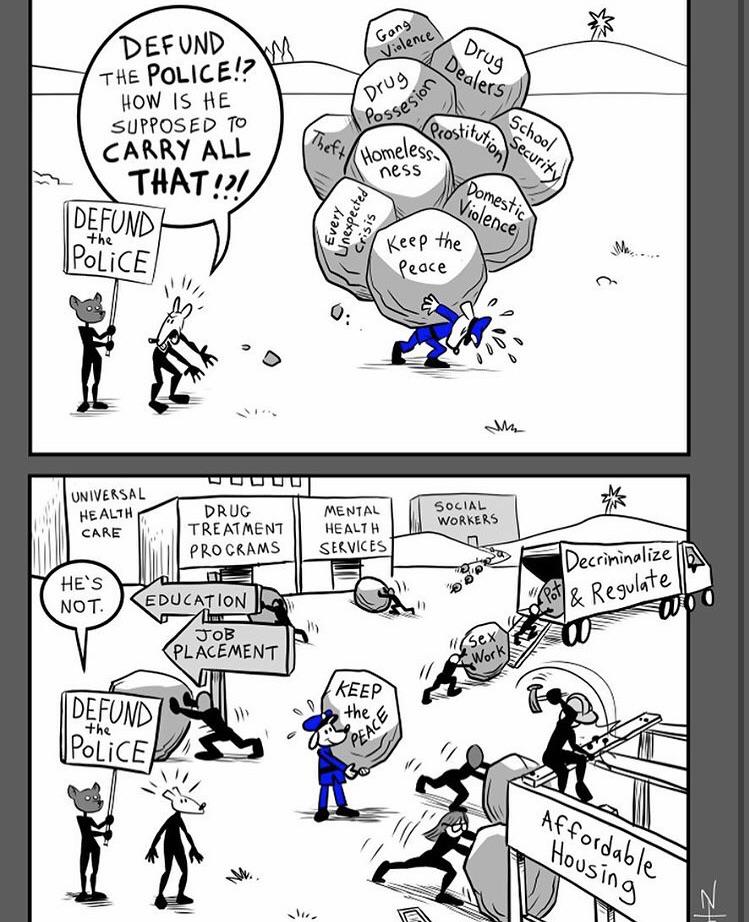

I love this comic by Neal Skorpen that illustrates how some conversations that are construed as “anti-police” are actually just trying to explore a new paradigm where police (who are often underpaid and overworked as it is) don’t need to carry such a heavy burden in our society.

At a hearing on these bills last month, KC Police Chief Rick Smith testified on the proposed legislation. One of the things that he bemoaned was that the Police Department no longer has enough officers to secure the route for a big annual race. Why do we utilize police to secure routes for a running event? Can’t we utilize the same type of security companies that staff concert venues to secure a race route?

One common conversation related to “defunding the police” is around responding to mental health crises in the community. Cities are hoping to build teams of social workers who can respond to these frequent calls, perhaps in partnership with the police who could accompany the social worker to the scene if there is a threat of violence and ensure everyone’s safety before allowing social services to proceed with an assessment and service provision or referrals.

There are many great examples of proposals to civilianize responsibilities that are currently held by police officers. There is an incredible paper in the Stanford Law Review that outlines a framework for decoupling traffic enforcement from police function, a proposal that is being considered in a number of cities around the country. There are experimental programs underway for cities to dispatch civilian teams to offer services to unhoused individuals rather than have police address issues like panhandling or encampments. And there are many education advocates who are seeking alternatives to utilizing law enforcement officers in K-12 school settings.

This would free up the police to focus on tackling violent crime in our communities, which is where they are of the greatest value. I think that it is very possible that it could also greatly improve community trust and respect for police, which is unfortunately at an all-time low. However, we are at a moment where most conversations about this topic are immediately shut down because of an assumption of bad intentions or “anti-police” sentiment.

Prioritizing Anti-Poverty Policies as Crime Prevention Tactics

In addition to reconsidering the most pertinent roles for police in society, there is also an important conversation to be had about preventing crime through addressing poverty.

As an anti-poverty policy organization, Empower Missouri holds a strong belief that crime is often a symptom of poverty. Some people break the law in a desperate attempt to provide for their families. Others live in communities, both urban and rural, where there is an abiding sense of hopelessness; the disinvestment and poverty in these communities is often overwhelming. For example, in Jackson County (which comprises most of KC), 15% of residents live below the federal poverty line (FPL) ($12,800 for one person; $26,500 for a family of four) and nearly 40% live below 200% of the FPL ($25,600 for one person; $53,000 for a family of four).

Communities ravished by poverty can become breeding grounds for drug use and crime. We can choose to address these issues through policing, or we can seek to address the root cause of the issue, working to ensure that every Missourian has an equal opportunity to thrive. Reallocating dollars from law enforcement to programs aimed at decreasing poverty and preventing crime is smart policy. This includes investing in the expansion of affordable housing, universal pre-K, affordable 24-hour childcare options, community health initiatives, substance abuse treatment programs, community colleges, job training programs and mental health services. Decreases in poverty will mean decreases in crime. It is important not to conflate these efforts with “defunding the police” or “abolishing police.”

We urge advocates, local leaders, Missouri legislators, and law enforcement agencies to approach this important conversation with respect, humility, and the assumption of good intent. We can both respect the efforts of law enforcement and also want to try different approaches to preventing and addressing crime across our state, including ameliorating poverty.

Want to join the conversation? Sign up for our Friday Forum on the issue on Friday, February 18th at noon!